Habit Tracking. It’s a really popular trend in bullet journaling, despite not being part of the original rapid logging system. And it’s that way for a reason: people like to see the progress they’ve made, or habits they’ve kept up with. Sometimes they’re functional or necessary, like taking medication or tracking the number of hours you sleep. Sometimes, they’re aspirational, like workout trackers or recording the number of pages you write every day. There are tons of activities you can track and many ways to track them, both physical and digital.

I use a few trackers to look at what I do every day. One of my favorite things to do is look at past habit tracker pages to see what I was doing at any given week (and with a discbound planner system, I can actually pull all the habit tracker pages out and look at them together)!

In the beginning of 2019, I tried maintaining monthly and weekly trackers. By March, however, I had completely switched over to weekly trackers—I just don’t have the patience to keep flipping back to update a monthly tracker!

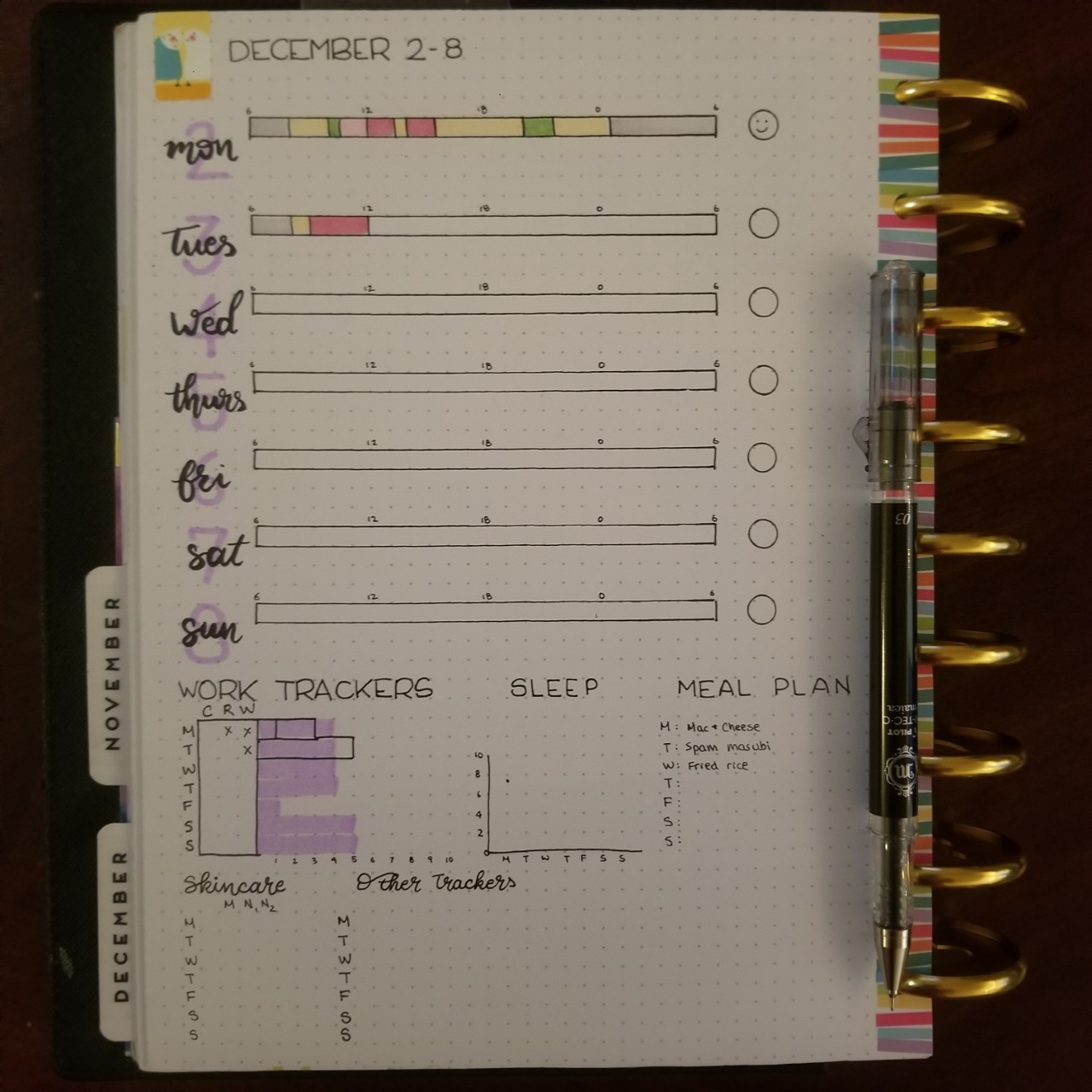

Here’s a template of the weekly tracker page I use now. On the top of the sheet is my time log, on the bottom is a group of other trackers. (Disclaimer: this picture, and all the pictures in this blog post, are not real. While I do use this habit tracking template, I am not using real information to fill out the time log or habit trackers below).

An example of a weekly habit tracker page.

The Time Log

On the top half are time trackers (sometimes known as a time log, since 1 page has 7 time trackers). Each row has 24 boxes: one for each hour of the day. My days begin at 6 a.m. and end at 5:59 a.m. the next day, so the first box of the day is 6 a.m. to 7 a.m.

An example time log. In this example, I am midway through my Tuesday.

I use a combination of seven or eight colors to identify out what I’m doing at any given point. Sleeping (which is grey), “down time” (orange), and meetings (purple) are common things to track. I also track reading (pink), writing (red), programming (blue), hand coding (light blue), and “misc work” (green). These more detailed codes allow me to really see where my work time is spent on any given day.

Writing, in particular, involves a lot of different tasks. The three that are the most common for me are: outlining, new writing, and proofing. If I want to provide more detail about what I’m doing when I’m “writing”, I’ll mark a box with “O” for outline, “W” for new writing, and “P” for proofing.

Underneath each time tracker, I will write notes and details about that day, things that add context to the day’s data. This includes (but is not limited to): social functions I attend, exam days, major grading days, conference deadlines, travel days, and sick days.

Other Trackers

Below my time log are templates of a few other trackers. I don’t actually use all of these; I just wanted to present different ideas of trackers you may be interested in.

Some example trackers. In my day-to-day, I do use the work tracker and the skincare tracker.

Work Tracker

I do use a work tracker: it’s a 7x3 matrix, with each row representing a day, and each column representing a task (c = coding, r = reading, w = writing). While I already track these tasks in my time log, they’re important enough that I also want to record when I do all three daily; I like day when I code a little, read a little, and write a little.

To the right of this 7x3 matrix is a set of purple bars. Those are the number of pages I hope to write daily (my estimate). I draw a rectangle to represent the number of pages I write in a given writing session (my observed)—1 box for 1 page, 3 boxes for 3 pages. This allows me to see the days I’ve hit my writing goals… and the days I haven’t.

The combination of my time log and my writing page tracker allows me to see how much I’ve written per hour. Sometimes, the words flow out easily and I can write 1 or 2 pages in an hour. Sometimes, it’s really hard to produce good writing.

Other Trackers

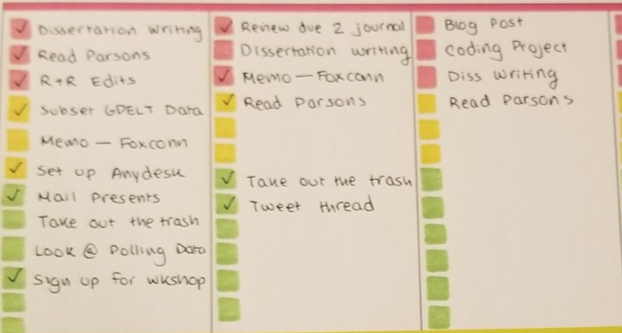

I do track a variety of other, non-work tasks. These range from the mundane habits, like brushing my teeth or showering, to hobbies, like baking and doing calligraphy.

For most of these tasks, each box represents one task per day (similar to my work tracker, the columns are the tasks and the rows are the days). It’s easy to vary up these tasks based on my needs that week, or things that I want to improve on. For that reason, the list of habits that I track change week-by-week.

Sometimes, I want to keep track of a more complex habit (e.g., taking multiple types of medication or my skincare routine). For this, I’ll often use a frankenlog system.

The Frankenlog

The goal of the frankenlog system frankenlog system, generally, is to jam as much information into a single page of your bullet journal. This is a great, minimalist strategy that gives you a “bird’s eye view” without sacrificing the detail.

One of the awesome features of the frankenlog is the “four mark” daily habit box. Each habit is tracked with a single pen stroke, allowing for four habits to be tracked with one box.

I use this system to track my skincare routine. In the morning, I have four tasks: face washing, toner, vitamin c extract, and sunblock. In the evening, I have seven or eight tasks: face washing, micellar water, toner, face mask (sometimes), eye cream, hyaluronic acid serum, retinol, and night cream.

An example of a frankenlog habit tracker. Each “box” can track up to four different tasks or habits. In this skincare example, I have 4 morning steps and 8 nighttime steps.

Weekly trackers give me a good sense of what I’ve been doing that week. This helps me make sure I’m living a (relatively) balanced life—time for work, for friends, and for myself. Plus, I love to see the bars fill up over the course of the week.

Example time lapse of a week’s worth of habit tracking information.