About a month ago, I ran across this funny tweet about people buying Faraday Cages or mental router covers to block 5G:

I got really curious about what the Amazon reviews cumulatively looked like, so I did a small data collection of reviews from 33 different “Faraday cages” (and bags).

For folks who are unfamiliar with Faraday cages, these are encasings (typically of conductive mesh) which are used to block whatever is within the cage from electromagnetic fields. If put around a router, a Faraday cage would naturally block out all internet signal (and if it doesn’t, it wouldn’t actually be a Faraday cage). In other words, buying a Faraday cage to enclose your wireless router would defeat the purpose of having a wireless router.

Amazon Faraday Cages & Router Guards

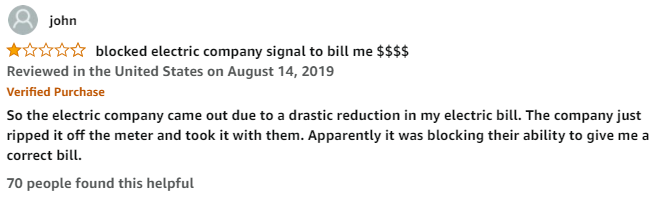

Though attention to Faraday cages and router guards on Amazon appears to be pretty recent, some of these things have been sold on Amazon for several years. Pre-2020 reviews show that people initially bought these wanted to cover smart meters, which are often installed by electricity suppliers.

More recently however, people have been purchasing these covers to block from 5G Routers. In fact, there has been a notable increase in the number of verified reviews about these products.

Throughout the time span, verified reviews of the products range greatly from folks who are convinced that using a router guard has deceased their headaches/improved sleeping to people complaining that the product has made using the internet impossible. One common feature of the positive verified reviews was an emphasis on how the guards would block elites (electric companies and governments) from “getting inside my brain.”

However, there were also reviews of folks complaining that their internet was no longer accessible.

Another big reason why some of the Faraday cages/bags were poorly reviewed was that they were too small for routers. This was an especially common critique when people wanted to use cages for smart meters to cover their router.

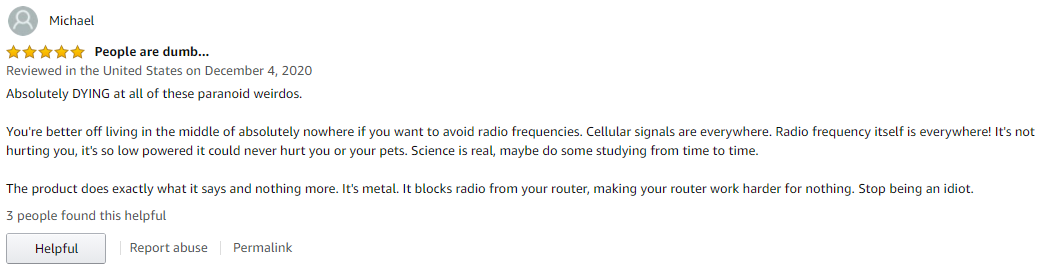

Unverified reviews typically took on two types of flavors: (1) mocking those who had genuinely bought the product or (2) corrective information that tried to explain why these products are basically pointless. Notably, since the December 2, 2020 tweet, the number of unverified reviews has grown considerably.

Unsurprisingly, the most common positive sentiment words (when using the Bing sentiment dictionary) focused on its ease of use and how it “worked perfectly” (this was said both sarcastically and genuinely). Negative words either focused on the “harmful” effects of electromagnetic fields (headaches, cancer, etc.) or criticized the cages for being a scam or joke.

Though the results were pretty unsurprising, this was a good exercise in playing around with Amazon reviews! Plus, with my first semester of teaching over, I’m hoping I can be a more active blogger.

The data and code for this analysis can be found on my github, here.

![Amazon Product: [Upgraded] Smart Meter Cover RF Radiation Shield | Independently Tested and Shown to Reduce 95-98% RF Radiation from Smart Meters | USA Company](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/573e619937013b2055692e37/1608945833728-S7IU0XMVRRLF7PDGBOP1/review_2.png)